Is bed rot really that bad?

Oxford University Press’s word of 2024 was “brain rot.” The year also gave us a flurry of TikToks documenting “bed rotting.” What’s with all this rotting — and is it a trend we should be taking into 2025?

But first: What do these terms, generally used by Gen Z-ers and millennials, even mean? “‘Brain rotting’ typically refers to the idea of engaging in mindless content consumption, like scrolling social media or binge-watching TV shows, which over time, feels like numbing or dulling your brain,” explains mental health therapist Brittany Cilento Kopycienski, who owns Glow Counseling Solutions. “‘Bed rotting’ involves spending excessive time lying in bed, contributing to physical and mental stagnation.”

Both activities, it seems, are about checking out of whatever your reality is at the moment — and checking into the often-good feeling of doing nothing. Is that good for our mental health? Here’s what experts say.

Why are we so drawn to ‘rotting’?

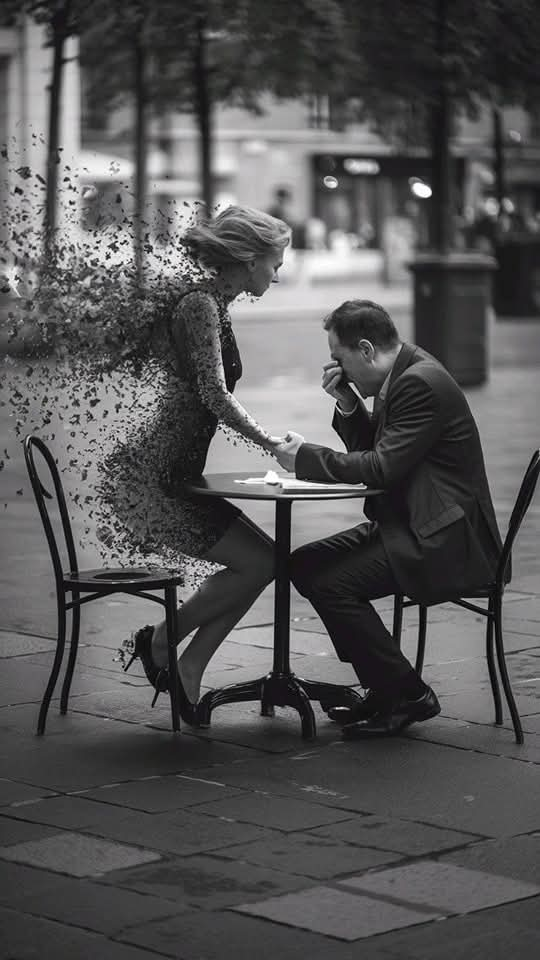

“Let’s face it—bed rotting or brain rotting is not a style of lazy living. It’s about escape,” psychologist Caitlin Slavens tells Yahoo Life. “The world is noisy, chaotic and often overwhelming. ‘Rotting’ is like pressing a giant snooze button on life. When you’re inundated with expectations (of work, family or even yourself), shutting down might seem your only option.”

She adds, “These trends are a response to a world that’s made us feel like we must be performing in every moment of our lives — for work, for social media, for each other’s expectations. The rise of rotting says we’re burnt out, together.”

That may be especially true for younger adults. “Our brains are experiencing unprecedented levels of stimulation through constant notifications, social media and digital engagement,” Sophia Spencer, a social psychology and mental health therapist, tells Yahoo Life. “For Gen Z and millennials in particular, they are the first generations to live like this from a young age and for this to be their norm. Essentially, their brains are subject to a level of information that was once unthinkable, and not what our brains are designed for.”

But others argue that this urge to disassociate from life isn’t new, but rather something past generations have also felt as they settle into adulthood. “Do you remember the ‘adulting’ movement?” Slavens points out. “People began to celebrate even the most basic life tasks, like doing laundry or paying bills, as if they were a win in a world so large it felt overwhelming. Or hygge — the Scandinavian midcentury concept of warm living — where we all collectively agreed that it was candles and blankets we needed to feel better when burned out. “All of these trends speak to the same need: to ease up, to take a breath, to feel fine about not doing it all.”

Is rotting a bad thing?

It really depends on the intention behind it — and how much time is being spent staring at screens in lieu of actually resting. Many people see bed rotting as a particular form of self-care: a day spent in bed, with a sole focus on recharging. “Our brains are not meant to be on overdrive all the time. Intentional breaks, time away from screens and the permission to veg out can be restorative,” says Slavens. “The issue is when rotting turns into avoidance, when we’re evading responsibilities or feelings we’re afraid to confront. So yes, a little rotting? Great. Full-blown decay? Probably not ideal.”

As for “brain rot,” who among us hasn’t mindlessly scrolled on our phone? “‘Rotting’ in moderation can be seen as a chance to mentally reset,” says Kopycienski. “It can allow for a break from constant stimulation where emotional recovery can occur.”

How do we move forward?

Thinking all this rotting through, the long and short of it seems to be that it’s about burnout. And burnout isn’t best handled by festering, or rotting; it’s best handled via intentional rest, experts say. “The best thing we can do is redefine what rest looks like in a digital age,” says Spencer. “Rather than reactively rotting, [we should be] having a system of proactive healthy habits.” That might involve proactively setting better work-life boundaries, scaling back our commitments or being less online to minimize burnout in the first place. Spencer doesn’t rule out more radical change.

“When our ancestors went through significant social change, such as during the Industrial Revolution, people moved from agricultural rhythms that followed daylight to the factory 9–5 schedule,” she notes. “I think we need to take the digital age as a significant change to our life … and adapt our lives ourselves as appropriate.”